Red, blue and yellow

The use of color in anatomical illustration

July 23, 2015

Each fall the Alberta Medical Association Representative Forum/annual general meeting features the Dr. Margaret Hutton Lecture Series. Medical students present on various interesting aspects of medical history. To share their excellent research and conclusions, we are carrying the highlights of the lectures in Alberta Doctors’ Digest.

This issue features Scott Assen of the University of Calgary.

Color is both symbolic and practical

Modern anatomical illustration uses color both symbolically and literally, often with the aim of overlaying function on an accurate structural representation, as represented for example in the central atlases of The Classic Collector’s Edition – Gray’s Anatomy. The established convention of red for arteries, blue for veins, and yellow for nerves aids students of anatomy to orient themselves quickly and effectively. In vivo, however, these structures are not so clearly defined. Arteries and nerves appear white, and veins appear whitish-blue. So how did this convention come about? To answer this question, we must examine the historical circumstances of anatomical illustration, from the middle ages to the modern period.

Early anatomy pre-color

Prior to the first uses of color in anatomical illustration, value gradations were approximated with techniques such as stippling and cross-hatching. In the era before the Italian anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514-64), most anatomical illustration was schematic in nature and was primarily concerned with confirming previously known facts. A notable exception is Marcantonio della Torre (1481-1511), who established a school of anatomy in Pavia, in what is now Italy. Della Torre employed the famous artist Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) as an illustrator, and while none of della Torre’s texts have survived, da Vinci’s anatomical sketches are notable both for their accuracy and their beauty. Da Vinci worked from cadavers he personally dissected, marking a tightening in the gap between subject and depiction. The goal of da Vinci’s anatomic work was, however, to further the graphic arts, rather than to benefit anatomic science.

The turning point in early anatomic illustration is marked by Vesalius, and his marvellous De humani corporis fabrica, published in 1543. This influential work was written and illustrated directly from human dissection, ushering in a revolution in anatomy and toppling the teachings of Galen, who worked from animal models. Vesalius’ anatomical illustrations were woodcut monochrome engravings, notwithstanding a special copy given to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V (1500-58), which was hand-colored. This edition features arteries and veins colored with red and blue, with frequent reversals of color in the same vessel. This is perhaps unsurprising given that the physiology of circulation was discovered in 1651 by the British surgeon William Harvey (1578-1657), some hundred years later.

The first color prints

The first color-printed medical illustrations were published in 1627 by Gaspare Aselli (1581-1626), a physician and professor in Pavia. Aselli discovered the lacteals accidentally while vivisecting dogs. He noticed that recently fed dogs had an engorged network of whitish vessels throughout the intestinal mesentery. His publication of this discovery included color-printed illustrations of the canine intestine, mesentery and liver. The woodcut plates used four colors: black, red and two shades of brown, with the white of the paper representing the lacteals. It is worth noting that the red used for the mesenteric vessels corresponds with their appearance in vivo, due to their relatively small calibre. Thus, Aselli’s color scheme is a literal use of color, rather than the symbolic use we see primarily today.

Wax injection and symbolism

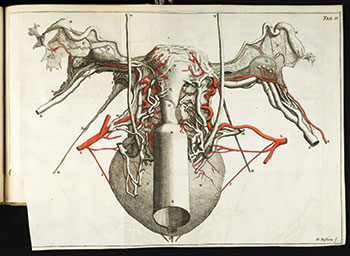

Aselli’s color printing technique was lacking in detail and laborious in its use, and so fell by the wayside in favor of the established monochrome woodcut printing method. Dissecting techniques, however, continued to improve, and in 1672, Jan Swammerdam (1637-80), a Dutch physician, published a work on the anatomy of the uterus. The text contains a description of Swammerdam’s red wax injection process, which was used to improve the visibility of arteries. The accompanying images are hand-colored and showcase the first truly symbolic use of color in anatomic illustration.

Swammerdam showed Frederik Ruysch (1638-1731), a Dutch anatomist, the wax injection process. Ruysch used the technique to dramatic effect, creating macabre dioramas involving fetal skeletons, wax-injected organs and even preserved insects. He came to amass a great collection, not unlike the plastinated body exhibits of today.

Mezzotinting: a new method

High-quality color printing advanced again in 1704 with an innovation from Frankfurt-born Jacob Christoph Le Blon (1667-1741). Le Blon developed a three-color mezzotinting printing method using three different impressions of one image, printing in blue, yellow and red. By combining these colors, Le Blon was able to print any other color, including black. He published one known anatomic plate of male genitalia. It is, however, exceedingly rare, because Le Blon was a poor businessman and his printing venture quickly went under. Luckily, Jan Ladmiral (1698-1773), a pupil of Le Blon’s, picked up the technique (and claimed sole credit for it). He was employed by Bernhard Siegfried Albinus (1697-1770), a famous anatomist in Leiden, to make a print of a section of intestinal mucosa, published in 1736. The arteries of this specimen had been injected with red wax, and the veins with blue wax. Correspondingly, the red and blue mezzotint plates contained the entirety of the arteries and the veins, respectively. In this way, blue veins were used symbolically for the first time.

Over the next several decades, another student of Le Blon’s, a Frenchman named Jacques Fabian Gautier d’Agoty (1716-85), published anatomical plates using the color mezzotint method. D’Agoty also claimed erroneously to have invented the process himself. His anatomical renderings were of inferior quality, useful to neither the physician nor the artist. He did however depict the nerves and chose the more literal white to represent them.

The rise of color symbolism

In a similar time period, Christoph Jacob Trew (1695-1769), a physician and naturalist from Nuremberg, published a painted depiction of a knee with red arteries and yellow nerves. Trew used color to great symbolic effect in his work. He was the first to color the unique bones of the skull to aid students in orienting themselves, a technique that can be found in almost every anatomy atlas since.

Lithography

Trew’s yellow nerves did not catch on, however, and abundant examples can be found of the symbolic use of white for nerves upon the adoption of lithography as a printing technique. Lithography was invented in the 1820s in Germany and enabled the mass production of high-quality color prints. Its adherents include the Italian anatomist Paolo Mascagni (1755-1818), French anatomists Jules Germain Cloquet (1790-1883) and Jean-Baptiste Sarlandière (1787-1838), and the English anatomist George Viner Ellis (1812-1900), all of whom depicted arteries in red, veins in blue and nerves in white.

Henry Gray and yellow nerves

It was not until the late 19th century that depictions of yellow nerves began to gain traction. The seminal textbook Anatomy of the London anatomist Henry Gray (1827-61) was first published in 1858, but early editions had monochrome illustrations, depicted in a dry, clean, institutionalized style. It was not until the confusingly-named 1887 New American from the Eleventh English Edition was published that color was used. In fact, the illustrations remained mostly monochrome, with only arteries, veins and nerves colored in red, blue and yellow respectively. From this point forth, anatomy texts and atlases continued with this convention – for example, the popular and beautiful anatomical illustrations of the New York surgeon Dr. Frank H. Netter (1906-91) that are frequently used today are no exception.

Conclusion

The symbolic use of color in anatomical illustration is, of course, intimately interwoven with the general history of anatomy and the history of color printing and publication. Crucial factors influencing the adoption of the modern convention for coloring vessels and nerves include the wax injection process used to highlight the vessels during dissection, primary color use in three-plate color printing, and the increased awareness of the utility of color use in orientation and education.

References available upon request.